Hoani Waititi Marae was opened on

April 19 1980, its purpose is to provide a centre for Māori, language, culture and practice.

A place of learning that provides a Māori perspective on the world. Hoani Waititi Marae is named after Hoani Retimana Waititi, a descendant of Te Whānau-a-Apanui, Kauaetangohia. His legacy is honoured through the formation of a Kōhanga reo, Kura Kaupapa Maori and Whare Kura houses, Kapa Haka groups, Te Whare Tū Tauā o Aotearoa houses of Maori lore. The Marae complex itself is the result of goodwill by the community of west Auckland, schools and iwi from around the country and the world.

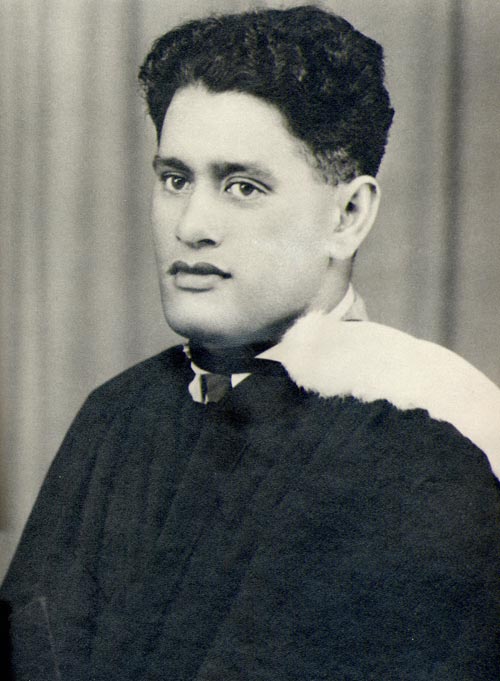

Born 1926 - 1965

Hoani Retimana Waititi

Hoani Retimana Waititi, known as Johnny to his many friends, was only 39 when he died, but his short life was packed with achievement and his ideas, energy and humour were an inspiration to his people.

He was born at Whangaparaoa, near Cape Runaway, Bay of Plenty, on 12 April 1926, the son of Kuaha Waititi, a farmer, and his wife, Kirimatao Heremia Kerei. Both parents were of Te Whanau-a-Kauaetangohia of Te Whanau-a-Apanui, and his mother had connections with Ngati Awa. Hoani’s father also belonged to Te Whanau-a-Te Ehutu, Te Whanau-a-Pararaki and Te Whanau-a-Kahu hapu of Te Whanau-a-Apanui. Hoani’s paternal grandfather, Manihera Waititi, had a strong influence on his grandchildren; he was an important community leader, learned in Te Whanau-a-Apanui tradition, and sometimes consulted by Elsdon Best. He believed that education was not only to be obtained in European schools, but also in whare maire (Maori schools of learning), and that both were essential for Maori.

Hoani Waititi was brought up in a strongly Anglican household where Maori was the first language. The family was poor and life was hard. He travelled on horseback to his first school at Whangaparaoa, and in 1939 and 1940 went to St Stephen’s School at Bombay, south of Auckland.

Returning home from his first term there, he made the mistake of using some of the bastardised Maori popular among a number of his school mates. He benefited, however, from the angry scorn of his family and from the teaching at the college, and developed a rich and expressive Maori vocabulary. While at St Stephen’s he won the Buller Scholarship, and from 1941 to 1943 finished his secondary schooling at Te Aute College. In 1943 he passed Maori I as an extramural student of Victoria University College. In February 1944, aged 17 (but claiming to be 19), he joined the Royal Air Force and began flying training. In February 1945 he transferred to the 28th (Maori) Battalion and served in Italy. He then went with Jayforce to Japan and was discharged in October 1946.

In 1947–48 Waititi trained as a teacher at Auckland Training College and resumed studying for a BA at Auckland University College; he graduated in 1955. During early 1949 he taught at Te Kaha Maori District High School and at Nuhaka Maori School in Hawke’s Bay. He was based from 1949 to 1957 at St Stephen’s School, but also taught Maori at Queen Victoria School for Maori Girls and at Auckland Girls’ Grammar. In 1957 he became a Maori-language officer in the Department of Education, and in 1963 was seconded as assistant to the officer for Maori education, D. M. Jillett. In the late 1950s and early 1960s he continued to teach, but also lectured at Ardmore Teachers’ Training College, at the adult education centre of the University of Auckland, and in the Maori class at Mount Eden prison.

He spearheaded a back-to-school movement among Maori adults, personally encouraging and assisting many to acquire School Certificate. During these years he was chief examiner of Maori in the School Certificate examination, and worked on developing new teaching techniques. Co-operating with the Maori Language Advisory Committee, he wrote two volumes entitled Te rangatahi (1962–64). These language courses were to become the standard texts for learning Maori at all levels, including university, for decades. They avoided grammar rules, substituting a sustained use of increasingly complex grammatical constructions. Through a gradually expanded vocabulary and the adventures of their main character, Tamahae of Te Kaha, students were introduced to Maori rural life, expanding in Book 2 into the urban environment and the wider world.

Waititi became involved in a vast range of activities, at one time or another finding time to contribute to nearly 80 organisations. These included the university Maori club (of which he was a president and patron); the anthropology and Maori race section of the Auckland Institute and Museum (of which he was a president); the Polynesian Society; the Auckland Regional Committee of the Historic Places Trust; and the Boystown Police and Citizens’ Committee.

He compèred many concerts at the Maori Community Centre. He was president of the Mangere Marae Society, an executive member of the Akarana Maori Society, and co-chairman for the Auckland region for the Maori Education Foundation. In 1962 he delivered some 96 speeches to raise funds for the foundation and to explain its aims. He also spoke to numerous organisations on race relations, Maori history, Maori problems and a wide variety of other topics.

Although a practising Anglican, Waititi raised funds for the Auckland Maori Catholic Society for their new centre, Te Unga Waka, and sponsored the activities of Mormons, Presbyterians and Methodists. His wide circle of friends included writers, artists, photographers, and the governor general, Sir Bernard Fergusson, whom he advised on ‘all aspects of Maoridom’.

He led campaigns to raise money to help struggling Maori sports figures, academics and artists to gain experience overseas. Most notable among these were the tennis player Ruia Morrison, golfers Walter Godfrey and Sherril Chapman, table tennis champion Neti Davis, artist Ralph Hotere, singer Kiri Te Kanawa, and Pat Hohepa, who was to achieve his PhD in linguistics in the United States. From the late 1950s Waititi worked with Maori in prison, forming the Maungawhau Maori Culture Group at Mount Eden prison.

Possessing no vanity and no ambition, Waititi gave himself with generosity and tremendous energy and enthusiasm to his current cause. His manner was the same whether he was visiting a prison or Government House. At a time when his contemporaries in education tended to rely on corporal punishment and formal discipline, he was a big brother to his students, inspiring them with enthusiasm and infectious fun.

He was a non-censorious and understanding brother to his friends in prison, and when they emerged, ‘Johnny’ would be there to ease their first contacts with family and employers. He had a passion for sport, representing Auckland at softball and table tennis. He was a qualified tennis umpire and assisted with the administration of Maori rugby in Auckland.

Hoani Waititi did not marry. Within weeks of being diagnosed with terminal bone cancer, he died in Middlemore Hospital, Otahuhu, on 30 September 1965. After a service at St Mary’s Cathedral, Parnell, conducted by Bishop E. A. Gowing, his body was carried home for burial at Cape Runaway on 5 October.

An outpouring of grief from all who had known him was expressed in letters and articles in the press and in waiata. The Marae is named is his honour after consultation with his whānau of Kauaetangohia, Te Whānau-a-Apanui. Hoani Waititi Marae, the whānau and community continue to uphold his legacy of Maori education, equal opportunity and unity as the foundation of building a better Aotearoa.